Dissecting the Controversy of Pernkopf’s Anatomy

- Maggie Sheridan

- Oct 3, 2025

- 4 min read

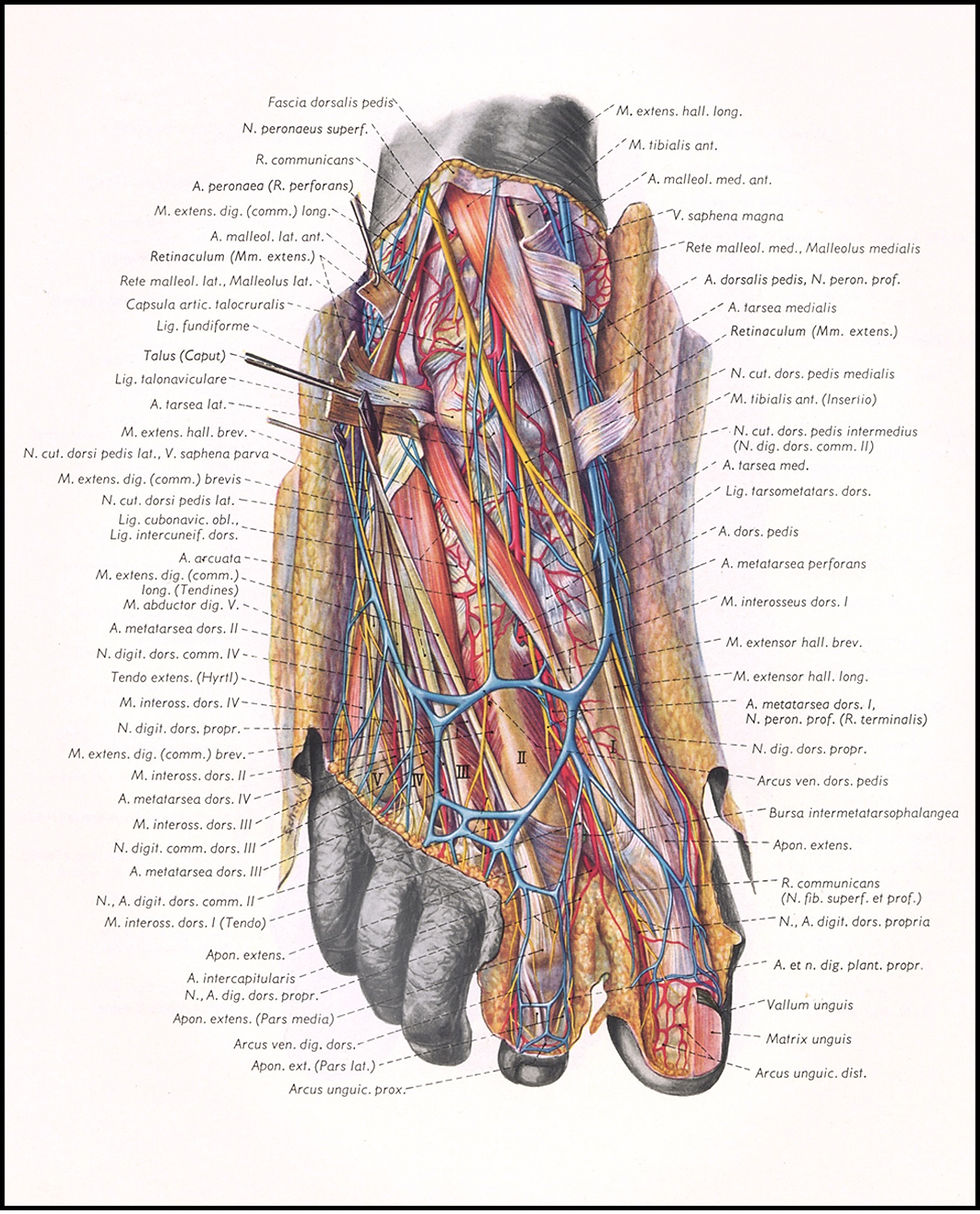

Pernkopf’s Anatomy, an anatomical atlas comprising 791 watercolor paintings across four volumes and seven books (1, 2), is renowned for its precise depictions of the body. Masterful use of color and minute detail make the images startlingly lifelike; to gaze upon a page is to be in thrall to its palpable physicality. Surrounding each drawing is an array of labels that pinpoint structures with unmatched specificity, creating a map worthy of its territory.

However, the text is tarnished by the troubling history of its creator and subjects. Eduard Pernkopf, anatomy professor and later president at the University of Vienna, spearheaded the atlas until his death in 1955. A devoted Nazi, he believed that science ought to serve the state’s aims by propagating the fit and sterilizing the unfit (3). Scholars’ discovery of Pernkopf’s Nazi Party affiliation, in addition to swastikas and SS runes in the artists’ signatures, raised suspicion that the cadavers dissected for the atlas had been Nazi victims (4). An investigation by the University of Vienna revealed that while none of the cadavers came from concentration camps, some had almost certainly been tried and executed by Nazi courts (1).

The investigation’s findings stirred ethical turmoil. Some thought that continued use of the atlas retrospectively justified Nazi abuses and constituted profiting off the victims’ suffering, while others argued that using the atlas to heal patients was the best way to honor the victims (3). The Vienna Protocol, written by Jewish religious authorities, ruled that using the atlas for clinical practice and education was acceptable to save lives (5).

But that does not absolve the medical community of the responsibility to learn the atlas’s history, to know that the cadavers were twice dehumanized—first by their unjust deaths and second by their unconsenting objectification as anatomical specimens. Unfortunately, this history is not widely recognized. Health sciences and other libraries do not have a uniform policy to educate readers about the atlas, with many libraries providing no context at all (6). In a survey of neurosurgeons, 41% were unaware of the atlas, and almost a quarter of those who were aware of the atlas did not know about its controversial past (7). Medical students were also found to lack awareness of the atlas, and after reading about its Nazi origins, students’ opinions were split on whether to use it (8).

Establishing a greater dialogue is required to disentangle the issues of power, respect, and remembrance that complicate Pernkopf’s atlas. Libraries can foster dialogue by adding a historical disclaimer, such as that written by the University of Vienna, to the atlas. In addition, all physicians take the Hippocratic oath, which delineates fundamental principles for the treatment of patients. To help fulfill these principles, physicians ponder real and hypothetical ethical scenarios during their training. Including Pernkopf’s Anatomy in undergraduate and/or graduate medical education would stimulate critical thinking and enable doctors to be better ethical stewards.

Moreover, studying Pernkopf’s Anatomy increases empathy. It challenges us to see research subjects, living and deceased, as not just sources of information but as real people. Their fate should be more than a footnote. Understanding the horror of the cadavers’ deaths and the era in which they occurred sensitizes us to the intersection between history, politics, society, and medicine, which helps us build more trusting relationships with those who have been hurt or marginalized.

Eduard Pernkopf’s atlas of anatomy is a work of rare skill and beauty, yet looking at it is a kind of voyeurism in light of the abominable deaths of its subjects and the hatefulness of its Nazi creators. It is a possibly lifesaving anatomical tour de force but institutionalizing it in the medical profession—swastikas and all—risks undue attention to, and perhaps complicity with, Nazi beliefs. It has great educational value, but libraries fail to adequately contextualize it and it is not widely taught. It would be a terrible error indeed to relegate Pernkopf’s atlas to a past we’d rather not revisit—because the past irrefutably shapes the present. Continued deliberation by librarians, physicians, medical faculty, and students is essential to determine how to responsibly use the atlas, and education on the atlas’s history will develop more ethical and empathetic providers.

Pernkopf and the cadavers gathered in the pages of his atlas are dead—but we are alive, and we must be vigilant of the forces that nurture life and the forces that harm it.

References

1. Angetter DC. Anatomical science at University of Vienna 1938-45. The Lancet. 2000;355(9213):1454-1457.

2. Czech H, Druml C, Müller M, Voegler M, Beilmann A, Fowler N. The Medical University of Vienna and the legacy of Pernkopf’s anatomical atlas: Elsevier’s donation of the original drawings to the Josephinum. 2021;237:151693.

3. Hildebrandt S. How the Pernkopf controversy facilitated a historical and ethical analysis of the anatomical sciences in Austria and Germany: a recommendation for the continued use of the Pernkopf atlas. Clin Anat. 2006;19:91-100.

4. Israel HA, Seidelman WE. Nazi origins of an anatomy text: the Pernkopf Atlas. JAMA. 1996;276(20):1633b.

5. Polak JA. “Vienna Protocol” for when Jewish or possibly-Jewish human remains are discovered. Boston University. https://www.bu.edu/jewishstudies/files/2018/08/HOW-TO-DEAL-WITH-HOLOCAUST-ERA-REMAINS.FINAL_.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed October 7, 2024.

6. Scheinfeld L, Saragossi J, Kasten-Mutkus K. A reconsideration of library treatment of ethically questionable medical texts: the case of the Pernkopf atlas of anatomy. Libr Resour Tech Serv. 2020;64(4):165-175.

7. Yee A, Coombs DM, Hildebrandt S, Seidelman W, Coert JH, Mackinnon SE. Nerve surgeons’ assessment of the role of Eduard Pernkopf’s atlas of topographic and applied human anatomy in surgical practice. Neurosurgery. 2019;84(2):491-498.

8. Coombs DM, Peitzman SJ. Medical students’ assessment of Eduard Pernkopf’s atlas: topographical anatomy of man. Ann Anat. 2017;212:11-16.

Maggie Sheridan is a fourth-year Medical Sciences major and aspiring physician at the University of Cincinnati. She is passionate about bioethics and medical humanities, and she believes that knowledge of history—political, cultural, and personal—is essential to improve medical practice. She can be reached at sheridmn@mail.uc.edu.

Comments